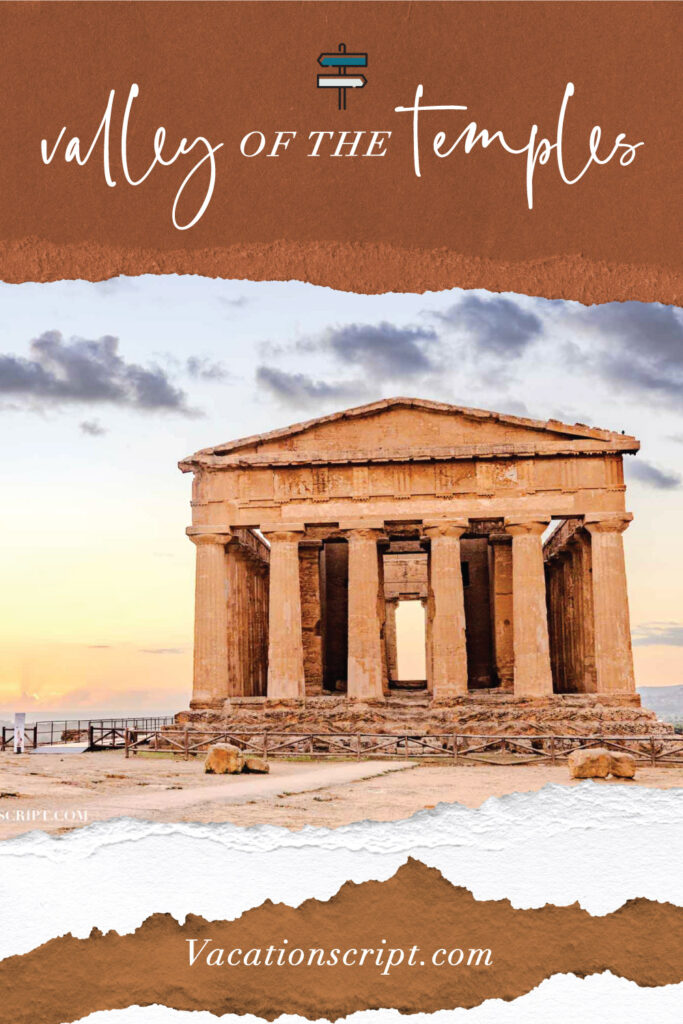

Imagine walking along a golden ridge, the Mediterranean glinting below, and around you rise the monumental silhouettes of ancient temples, still bearing the weight of centuries. That’s the essence of the Valley of the Temples, an archaeological site near modern Agrigento that was once the proud Greek city of Akragas. It’s one of Sicily’s seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Inscribed for its extraordinary collection of ancient Greek architecture, the site invites travelers into a living landscape where history and monumental stones whisper tales of myth and ancient human endeavor. So slip on your comfy walking shoes, bring your curiosity, and let’s wander through time.

But first, take a look at the map of Agrigento and the Valley of Temples below, and feel free to download a copy to your Google Maps. It also includes what to do in the town of Agrigento, as well as some nearby gems to be sure to check out.

If you’re looking for a simple add-on to your Agrigento itinerary, consider ending the day with a sunset aperitivo in nearby Licata. Set on a quiet hilltop resort overlooking the Mediterranean, the experience includes traditional Sicilian bites, bruschetta with the estate’s own olive oil, and a bottle of local wine—easy, relaxed, and perfectly timed with the evening light. Underage guests get a non-alcoholic aperitif, and the only thing not included is transportation, so you’ll just drive yourself and enjoy the view.

Valley of the Temples | Parking & Tickets

When preparing to visit this vast archaeological site, you’ll find two main entry points, each with its own strategy. You will want to set aside 2-3 hours to explore the Valley of the Temples.

Valley of the Temples Parking Lots:

My husband and I were a bit confused when we first arrived; some of the parking spots weren’t exactly ideal. But on our third try, we finally found a good one. Lucky for you, I’m breaking it all down so you can skip the hassle.

- On the western side | The lot at Parcheggio Porta V offers a large area to park, placing you at the lower end of the walk, and the ruins go from good to even better as you progress through. The ridge drops down toward the Mediterranean, so this entrance gives you the uphill walk early and a downhill stroll later. Just outside the entrance, a food stand is available to fuel your adventure, and a few souvenir shops offer items to browse or purchase, including hats to protect your face from the blistering sun.

- On the eastern side | At Parcheggio Giunone (near the Temple of Juno), there’s a smaller parking lot. Starting here means you’ll begin high, gaze over the ridge, then meander downhill through the site, which is ideal in the heat of the afternoon when downhill helps.

Valley of Temples Archaeological Site Entrance Information:

- Open Daily | 8:30 am- 7 pm (exit by 8 pm) and the spotlights turn on at 5:30 pm

- Price | €17 per person, or €23 per person for a combined ticket to include Kolymbetra gardens

- Reduced Admission | €10 per person for European Union citizens between the ages of 18 and 25, with ID

- Free Admission | National holidays & the first Sunday of each month, and for people under the age of 18

Tip: The paths are entirely exposed to the sun, so be sure to bring water, a hat, and sunscreen. However, if you forget, their shops offer a wide variety of products that tourists are looking for. In the height of summer, arriving near the time they open or planning a sunset tour is wise. The site also offers shuttle options for those with limited mobility or for saving tired legs.

Temple of the Dioscuri [AKA Temple of Castor and Pollux]

This post will guide you through the Valley of Temples, starting from the western lot and working your way uphill, as I believe this is a more rewarding experience. As you step into the valley, one of the first temples to grab your attention is the Temple of Castor and Pollux, also known simply as the Temple of the Dioscuri. The view: only four stately Doric columns stand upright now, weathered, tuff, and glowing in the afternoon sun, and behind them stretches the town of Agrigento in the distance; the past and present layered in one frame.

The Mythology behind the Temple of the Dioscuri

Meet Castor and Pollux, aka the Dioscuri—twin brothers straight out of Greek and Roman mythology, legendary for loyalty, courage, and brotherly devotion. But here’s the twist: one twin was mortal, the other divine.

Pollux was immortal, born of Zeus and Leda.

Castor was human, born of Leda and her husband, King Tyndareus.

Yep… twins with different dads. Confused? Let’s break it down:

One night, Zeus shows up as a swan (classic Greek god move) and seduces (or worse) Leda. That same night, Tyndareus also sleeps with her. Somehow, or magically, Leda ends up laying two eggs. Out hatch:

- From Zeus’s divine seed: Immortal twins Pollux and his sister, Helen (yes, Helen of Troy, famous for her beauty).

- From Tyndareus’s mortal seed: Twins Castor and his sister Clytemnestra (both fully human).

So, Castor and Pollux shared a mother but not a father, making them fraternal twins—one mortal, one immortal—but inseparable as brothers. Their story is all about duality: human vs divine, life vs eternity, and loyalty that transcends both.

And yes, Leda laying eggs sounds wild, but that’s Greek mythology for you. Gods could shapeshift, mortals could do the impossible, and eggs symbolized divine conception —a mark that her children were extra special.

Bottom line: Leda was human, a Spartan queen. Zeus was the swan, and together they produced the Dioscuri, after whom this temple is named.

The Sanctuary of the Chthonic Deities

If you didn’t know what you were looking at, you might walk right past this spot, as it looks like a scatter of ancient stones near the more photogenic Temple of Castor and Pollux. But beneath those weathered rocks lies one of Agrigento’s oldest sacred sites: the Sanctuary of the Chthonic Deities, devoted to Demeter and Persephone, the powerful mother-daughter duo from Greek mythology.

These goddesses ruled over the earth’s fertility and the underworld’s mystery—a balance between life, death, and rebirth that the ancient Greeks believed kept the natural world in motion.

This sanctuary was a terraced complex built into the slope of the hill. Archaeologists believe the first area was dedicated to the goddess of the harvest, Demeter. Nearby stood a smaller temple for Persephone, her daughter. She spent half the year in the underworld with Hades and half above ground, bringing spring to life. Their story symbolized the changing seasons and the eternal rhythm of growth and decay.

Here, worshippers likely brought offerings to bless their crops and honor the cycle of fertility. Clay heads and votive statues, some with serene, almost lifelike expressions, were found buried in the soil. One of these, a terracotta head of Demeter dating back to around 500 BC, is now displayed in Agrigento’s Archaeological Museum.

The second terrace, the best preserved, still shows traces of small temples and circular altars where sacrifices and rituals once took place. The third terrace, known as the Terrace of the Donari, was lined with statues gifted to the gods, overlooking what are now the green gardens of Kolymbetra below.

Kolymbetra Garden | A Forgotten Corner

I have been to the Valley of the Temples multiple times and have yet to explore the Kolymbetra Garden. I completely missed it the first time I was there, and the next time I arrived too late. It’s located next to the Temple of the Dioscuri, toward the greenery. If you see the sign above, you will know you’re getting close. You can add this location to your entrance ticket for a total of €23 per person. However, please note that the current hours may vary, as it opens later and closes earlier than the other attractions.

- Open March – June & October from 10 am- 6 pm

- Open July – September from 10 am- 7 pm [worst time to come to Sicily by the way]

- Open November – February from 10 am- 4 pm

Hidden among the temple stones (literally) is a little-known oasis: the Kolymbetra Garden. Once, this basin served as the enormous swimming pool of Ancient Akragas, fed by eighteen tunnels and aqueducts twisting through rock and earth. Centuries later, it has transformed into citrus groves, olive trees, and lavender beds, a living tapestry of Sicilian nature reclaiming sacred ground.

Picture stepping off the dusty temple path down into the refreshing shaded leaves of orange trees, where the hum of bees and the songs of birds play on repeat. This place lets you breathe, contemplate, and sense that this archaeological site isn’t just about stones.

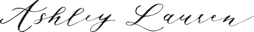

Temple of Vulcan [AKA Temple of Hephaestus]

You can only access the Temple of Vulcan by first entering the Kolymbetra Gardens.

Further down the ridge, you reach the Temple of Vulcan (also called the Temple of Hephaestus). It sits just beyond the lush Garden of Kolymbetra in the archaeological site and can feel like a side note compared with the showier monuments nearby.

You’ll walk through the Kolymbetra garden, then cross a railway line (no pedestrian crosswalk) to reach the temple’s plateau. Due to its tucked-away location and modest remains, it often escapes notice.

- The temple is likely the most recent structure built in the Valley of Temples complex.

- Architecturally, it blends a Doric style with subtle Ionic features (for example, the shafts display a faint Ionic influence).

- Inside the cella (the inner chamber), archaeologists discovered the foundations of an even older temple beneath, indicating that the spot had held sacred significance long before this building was constructed.

Mythology Behind the Temple of Vulcan

The name Vulcan (Roman) corresponds to Hephaestus (Greek), god of fire and forge. In legend, Vulcan was both a creator and destroyer. As a creator, he hammered weapons, armour, and jewels, powering the city’s prosperity. As a destroyer, he unleashed fire, volcanoes, and forging heat, symbols of cleansing or destruction.

In Greek myth, Hephaestus was an outcast, born lame and unwanted; he was hurled from Olympus by Hera. He fell for nine days and nights before striking the sea, rescued by nymphs who hid him in a volcanic grotto. There, surrounded by molten rock and smoke, he built his workshop, a place where imperfection became invention.

From his forge came the armor of Achilles, the chains that bound Prometheus, and the first woman, Pandora. The hammer blows of Hephaestus weren’t just noise; they were the sound of divine craftsmanship, fire made obedient to will.

When later cultures in Sicily identified him with Vulcan, they imagined his forge beneath Mount Etna, its eruptions the breath of his labor. So, when you stand before the broken stones of the Temple of Vulcan in Agrigento’s Valley of the Temples, imagine that divine workshop beneath your feet, where beauty, strength, and ruin all share the same spark.

The Temple of Zeus

And then we arrive at larger-sized scattered ruins that you can walk over and through—the Temple of Zeus, built to commemorate the victory of Akragas over the Carthaginians.

The Temple of Olympian Zeus in Agrigento’s Valley of the Temples once stood as one of the largest Doric temples ever attempted. However, never completed, it was unmatched in scale and symbolism. It stretched about 123 yards long and 61 yards wide, covering more than 6,000 square metres. It would have been amazing to see this temple in all its glory.

The Mythology of Zeus – King of the Gods

In Greek mythology, Zeus was the youngest child of the Titan Cronus and Rhea. Fearing a prophecy that one of his children would overthrow him, Cronus swallowed each newborn whole. But when Zeus was born, Rhea hid him in a cave on the island of Crete and gave Cronus a stone wrapped in cloth instead. Nursed by a goat named Amalthea and guarded by warriors who clashed their shields to drown out his cries, Zeus survived in secret.

With help from the Titaness Metis, Zeus tricked Cronus into drinking a potion that forced him to ‘vomit up’ the children he had once devoured—Poseidon, Hades, Hera, Demeter, and Hestia—each emerging alive and fully grown. The act became a symbol of rebirth and renewal, marking the rise of a new divine order. Together, the freed Olympians fought and defeated the Titans in the Titanomachy, a ten-year war that ended with Zeus crowned ruler of the heavens.

Sicily later entered his mythic geography. Ancient writers said Mount Etna was where Zeus struck down the monstrous Typhon, burying him beneath the mountain in eternal fury.

Telamon

The most striking feature of the Temple of Olympian Zeus in Agrigento’s Valley of the Temples is the colossal Telamon or Atlantes—stone figures that once appeared to hold up the roof itself. The ancient builders carved monumental men with arms raised and backs pressed against the walls, bearing the weight of the gods. The design drew directly from the myth of Atlas, the Titan condemned by Zeus to carry the heavens for eternity. Here, his burden becomes architecture and a fun place to stop for a photo.

Reliefs of the Gigantomachy, the battle between gods and giants, reinforced this same theme of cosmic victory, echoing Zeus’s dominion over chaos and Agrigento’s triumph over its enemies. One of these Telamons, re-erected on site in 2024 and standing nearly eight yards tall, now guards the sacred ground again.

Temple of Heracles [AKA Hercules]

Next, you will cross the pedestrian bridge into the eastern side of the Valley of Temples. Perched on a rocky ridge in the Archaeological Site of Agrigento is the Temple of Heracles, the oldest known temple in the valley. It was dedicated to Heracles (Hercules in Roman form), the legendary demigod famed for the Twelve Labours.

As you stand amid the eight surviving Doric columns, imagine a statue at the center, with the hero’s club and lion-skin iconography presented in marble, the city’s hopes invested in his myth. The temple’s elongated layout, broad capitals, and archaic proportions mark it as an early example of Greek sacred architecture in Sicily. Just below the site lies a Roman-era funerary monument, long misidentified as Theron’s Tomb.

The Mythology of Hercules

Meet Heracles — half man, half god, all chaos.

He’s the son of Zeus and a mortal woman named Alcmene, which already makes things complicated. Hera, Zeus’s wife, wasn’t thrilled about the whole affair (understatement of the century). So, she tried to destroy Hercules from the moment he was born by sending snakes to kill him in his crib. Baby Heracles? He just grabbed the snakes and strangled them like rattles.

But Hera wasn’t done. Years later, she drove him into a madness so deep that he unalived his own wife and children. When he came to, he begged the Oracle of Delphi for forgiveness. The answer: complete twelve impossible labors to atone for his crime.

These weren’t your average chores. He had to slay the Nemean Lion with skin no weapon could pierce, steal the Apples of the Hesperides from the edge of the world, and haul Cerberus, the three-headed dog of the underworld, up to daylight and back again. Every task pushed him beyond what was human—turning punishment into transformation.

By the end, Heracles wasn’t just a hero; he was a symbol of strength through suffering. He faced monsters, gods, and his own mistakes, and rose above them all.

It’s no wonder Agrigento’s ancient Greeks built a temple in his honor. Heracles represented what every mortal hoped for: the power to endure, and maybe, just maybe, to become something greater than fate intended.

The House of Alexander Hardcastle [ AKA Villa Aurea]

Here’s a human chapter in our story. In the early 20th century, an English army captain named Alexander Hardcastle purchased a villa near these ruins and dedicated his fortune to restoring the temples of Akragas.

Villa Aurea (also called the House of Hardcastle) sits between the Temple of Concordia and the Temple of Heracles, a reminder that the valley of temples didn’t die; it was lovingly revived. Imagine him, dust swirling around his boots, chisel in hand, financing excavations, drawing maps, waking the old gods.

His story adds a layer: the love of a single man for ruins becomes part of the living site. When you pass the villa, go inside and take a look; it has been turned into an art gallery. Then, go outside and explore the property of Villa Aurea. If your getting hungry follow the left side of the house to a restaurant before continuing on.

Temple of Concordia

Arguably the shining star of the site, the Temple of Concordia stands almost as it did nearly 2,500 years ago. Built around 430 BC, its 78 Doric columns rise to almost 19 yards at their tallest.

What sets it apart is that it was converted into a Christian church in the 6th century AD, saving it from complete ruin. The locals of Akragas, then Agrigentum, reused the ancient stone for new stories. As you walk around the temple, notice the subtle asymmetry, the traces of lime washing, and the sunlight slanting between the columns. It invites you to ask: How do we preserve the old and still make it new? This temple doesn’t just survive, it lives on.

Mythology of the Fallen Icarus

The sculpture Fallen Icarus is one of Igor Mitoraj’s modern reinterpretations of a myth as old as imagination itself. Inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses, it captures the moment after the fall — Icarus sprawled on the ground, his body broken, his wings torn away.

The story begins with Daedalus, a brilliant inventor, and his son Icarus, trapped on the island of Crete by King Minos. Escape by land or sea was impossible, so Daedalus looked to the sky. He built two sets of wings, crafted from feathers and beeswax, a father’s genius and hope bound together.

Before they took flight, Daedalus warned his son: “Don’t fly too high, or the sun will melt the wax. Don’t fly too low, or the sea will weigh you down.” But freedom has a way of clouding caution. As they soared above the waves, Icarus felt the rush of air, the thrill of flight, and ignored his father’s warning. The sun burned his wings. The wax melted. The boy who flew too high fell into the sea.

It’s not just a story of failure; it’s a reminder of what it means to reach beyond limits. Icarus became the symbol of every human who dares to chase freedom, even when the cost is the fall itself.

Le Mura & Arcosolia [AKA City Walls & Burial Arches]

Ahead of you is the le mura cliffline that once served as Akragas’ natural defense. In the Greek period, this sheer rock face acted as a wall long before anyone carved tombs into it. The arched cavities you see today, the arcosolia, came much later, between the 4th and 7th centuries AD, when the ridge slowly shifted from fortification to burial ground.

So what did the original defenses look like before time and later cultures reshaped them? The Greek wall once wrapped around the city in a massive circuit, built partly from carved bedrock and partly from stone blocks stacked in clean, regular courses. Over the centuries, the fortifications were reinforced with ramparts, towers, and hidden passages. Some gates connected directly to the sacred areas on the Hill of the Temples, linking the city to the coast. An internal road ran just behind the wall, giving soldiers a protected route for moving supplies during an attack.

As you walk, the landscape reveals these layers of history: the remains of defensive towers, the grooves of ancient roads, and the arched tombs carved centuries later into the cliff. It’s here more than anywhere else in the Valley of the Temples that you feel the site shift from sanctuary to city, and from city to necropolis.

Pick up a quick coffee from the stand across the dirt path before you continue.

Temple of Hera [AKA Temple of Juno]

The Temple of Hera, though sometimes called the Temple of Juno (the Roman equivalent). Built around 460 BC, it stands confronted by history: burnt by Carthaginians in 406 BC, restored by the Romans later.

At the highest point of the ridge, closest to the sea, it commands one of the most spectacular views in the Valley of the Temples. Without any barrier, the morning sea breeze blows towards the ground and the temple is pervaded by the salty smell of the sea air which permeates the atmosphere and characterizes the place.

Mythology That Fits the Landscape

Hera was the guardian of marriage, fertility, and the sanctity of the household, a goddess people approached when they needed protection, blessing, or justice. She could be fierce, unyielding, and sharply loyal. Placing her sanctuary at the cliff’s edge wasn’t just symbolic; it was strategic. From here, she “watched” the sea routes, the farmland below, and the entrance to the ancient city.

In Greek myth, Hera is the goddess who determines whether unions thrive or collapse, whether families flourish or fracture. What remains today is not just a temple but a presence: a commanding perch where mythology, topography, and ancient devotion align perfectly.

The Turn Everyone Misses: A Detour Through the Sensory Garden

At this point in the tour, you’ve walked the valley from end to end, but instead of retracing your steps back to the parking lot, this is where the experience turns. Keep to the right side of the dirt path near the Temple of Concordia and watch for the small sign that reads Garden of the Senses. Follow that path down and to the right, and suddenly the crowds thin, the noise fades, and the Valley of the Temples shifts into its quieter, more shaded atmosphere.

The Sensory Garden is a recent addition designed for true inclusivity, engaging sight, scent, touch, and sound in a way that feels both thoughtful and unexpected. Tactile paths & handrails help guide visually impaired visitors; panels with Braille and raised imagery tell the story through your fingertips instead of your eyes. Mediterranean herbs brush the air with familiar scents, shrubs rustle along the walkway, and small water features create a soft soundtrack that attracts local birdlife. It’s a subtle space, not grand like the temples, but it adds a warmth to the archaeological site, a reminder that the valley is still evolving, still finding new ways to welcome everyone who comes through.

Cardo I: Where the City Once Lived

You’ll pass a small sign marked Cardo I, which refers to one of the main ancient streets of Akragas. There’s nothing left of the houses that once lined it, except for the trace of where the road originally ran through the city. What survives now is a quiet stretch of cliffs, grazing goats, late-Roman tomb niches, and a few winding dirt paths.

It’s the part of the Valley of the Temples most visitors walk right past, but it’s one of the best places to feel how the ancient city blended into the landscape. Follow it to end up near the exit point past Villa Aurea.

Tomb of Theron Outside Valley of Temples

Despite its name, the Tomb of Theron has no connection to Theron, the 5th-century BC tyrant of Akragas. Travelers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries coined the name as they passed through the Valley of the Temples, a habit that stuck long after scholars clarified the monument’s true origins.

What you see today is a 1st-century BC funerary tower, built just outside the ancient city walls and designed to resemble a small temple. The tomb once belonged to the Giambertoni necropolis, not far from the Temple of Hercules, and for centuries it served far more practical purposes.

In the 18th century it functioned as a sheepfold for local sheep and the distinctive Girgentana goats that have roamed the ruins since medieval times. Early paintings—and later, 19th-century photographs—consistently show the structure surrounded by these animals, reinforcing how deeply the rural landscape shaped its story.

A guide once described the Tomb of Theron as “full of mysteries” and in learning more, it’s not hard to understand why. Much about its purpose and patron remains unresolved to this day.

Visitors should know you cannot access the Tomb of Theron from within the main archaeological site of the Valley of the Temples. Because the monument sits outside the ancient defensive walls, it can only be viewed from the road that forms the boundary of the park.

How to reach it:

• From the main parking lot, walk to the right along the main road.

• Continue until you cross the remains of Porta IV, the ancient primary gateway into Akragas.

• The tomb stands just beyond this point, marking the edge of the Roman necropolis of Giambertoni.

The Archaeological Museum

- Open Daily: 9 am- 7 pm

- Tickets: €8

Step off the ridge and into the Regional Archaeological Museum “Pietro Griffo,” the place where the Valley of the Temples comes into clarity. Built directly over the ancient agora, the museum blends the restored cloister of St. Nicholas with sleek modern galleries, creating a bridge between the city that was and the city we see today.

Inside are the pieces that once animated the temples:

• the Ephebe of Agrigento, a kouros with impossibly soft, carved surfaces

• black-figure and red-figure pottery pulled from ancient necropoleis

• a lion-headed waterspout that once funneled rain from a temple roof

• and the showstopper — an original Telamon from the Temple of Olympian Zeus, a giant stone figure that helps you grasp the true scale of that lost sanctuary

Each room moves through time, from prehistoric Sicily to the height of Greek Akragas and into the Roman era, but you don’t need to follow every panel. Pick one piece, let it anchor you, and then let the museum reopen the valley in your mind. It’s the quietest way to understand the world you’ve just experienced.

Essential Info for Visitors

Walking Distance | The “valley” is actually a ridge above sea level, and the walk from one end to the other is about 1.5 miles. For comfort, especially in hot months, start early.

What to bring | Comfortable shoes, SPF, a hat, and a water bottle (water fountains are available for refilling). The paths are rocky in places.

Getting There | As mentioned at the bginning, both Western & Eastern entrances have parking. From Agrigento town centre, you can also arrive via bus or taxi.

Why it’s Unique | At 1,300 hectares, the park of the Valley of the Temples is the largest archaeological site in Europe and the Mediterranean region.

Shopping | At the Valley of Temples shops you can find essential items like hats, water, and souvineers like magnets, and coins.

Where to Stay with a View of the Temples

For a stay that honors your long day in the valley with a great view of the temples, and an even better nights rest, consider these accommodation options.

One stand-out: Hotel Villa Athena, perched within the park’s boundary, near the Temple of Concordia. Imagine sipping your evening wine, blonde tuff stones turning pink in sunset light, temples glowing just beyond the terrace.

Budget Friendly: Il Giardino del Tempio offers comfortable, well-equipped rooms with garden views, private balconies or patios, and thoughtful amenities like a kitchenette, coffee machine, and on-site parking. Its location near the Valley of the Temples and central Agrigento makes it an easy base for sightseeing, and couples consistently rate it highly for convenience and hospitality.

Family Friendly: La Casa nel Tempio offers a comfortable two-bedroom apartment with a terrace, garden, and modern amenities including free WiFi and a fully equipped kitchenette. Its convenient location near central Agrigento makes it an easy base for exploring the area.

Like it, Pin it!

If you’re planning a trip to Agrigento—or even thinking about it—add this post to your Sicily board so you can come back to the details when you’re ready to explore the Valley of the Temples.